The first was “Brücke: The Birth of Expressionism in Dresden and Berlin, 1905-1913” show at the extraordinary and storied Neue Galerie, which I had always wanted to go to but had in the past grouped together with visits to the Met. However, after four hours at the Met, the only art you could really withstand afterward would be looking at senseless advertisement images on the subway ride home to nurse your newly numb, art-saturated thoughts. So I made the trek to the Upper East Side solely to see this show.

The exhibit focused on the origins of the German Expressionist movement with the group, Die Brücke, of which I had gleaned much interest in as an art history undergrad. But it is one thing to view a Kirchner or Schmidt-Rottluff mere inches away and quite another to merely read about the raw, thinly applied paint and edges that gave their group their radical signature. The disillusionment of urban life in Berlin prompted these would-be architects (except for the more traditionally trained Pechstein) to look toward new methods of expression.

Kirchner’s Street at Schönberg City Park (1912-13; shown above) was one of the first pieces to give pause due to its conspicuous lack of Fauvist color that came to represent Expressionism. It is the few vestiges of color, however, that give it its expressiveness. Aside from the signs of nature found in the green-leafed trees and the sky, the canvas becomes a backdrop for a play of overlapping color and texture, the gray, beige and whites of the streets melding into that of the buildings resting upon it. The streak-strewn sky is violently rendered as if violet-blue colored needles had been splayed across the canvas, threatening to pierce any errant fingers that dare approach. The ominous, dawn-tinted sky shrouds the piece as a lone woman in a purple dress appears at the center of the work, her flamboyant plumed hat and the late (or early) hour of day distinct indications of her salacious occupation. The three figures to the left and the couple to the right of the scene each include similarly-dressed women. The groups walk toward the left, potentially off of the canvas, out of our sight, and into an intimate encounter. The woman in purple is perhaps returning from fulfilling such an agreement, with her telling downward gaze and sloped shoulders. The unusual angle of the piece, wherein the scene is abruptly upended as if the viewer were suspended above it, is punctuated by the suggestive line of trees and the protruding sharply angled line of the buildings in an explicitly phallic manner. In the distance, we see an elevated train track with its plumed smoke, often a representation of industrial urban life, as a reflection of the woman’s hat and all that it symbolizes, and the culmination of a sexual act.

Having admired the raw energy of Kirchner’s many Berlin street scenes featuring prostitutes freely mingling with men amid expressive reds, purples and blues, it was quite striking to see the artist's distinctly different route in this work. However, these famous works must be viewed in context with any exhibition on Expressionism. In Berlin Street Scene (1913-1914), the central female figures (one enrobed in lipstick red, the other a rich royal blue) are clearly sex workers (modeled by two Berlin nightclub dancers, Erna and Gerda Schilling who appear repeatedly in his work), complete with conspicuous feathered hats, bright lipstick and rouge, and sharply defined (and suggestive) V-collared garments. The two men in the foreground dressed in marbled blues are often accepted as the artist. This can be supported by the characteristic cigarette dangling from the lips and the violently rendered hand of the figure, which is reminiscent of Kirchner's treatment of the limb in Self Portrait as a Soldier (1915), perhaps an allusion to his imminent military service and eventual denunciation of the brutality of war. The color of his deep red lips mirror that of the two women, perhaps symbolizing the artists' sympathetic view of these women’s plight and all that they represent to him: disillusionment of the pre-war era; the isolation and loneliness of modernity; and a public occupation and collective anxiety over industrialization, urbanization and class difference. Direct eye contact became the means of initiating a sexual exchange in such areas and this is telling in that the male figures in the background have their eyes to the floor. However, one of the street walkers looks at the figure presumed to be Kirchner as he looks toward the right and off the canvas, perhaps soliciting another female companion positioned off to the side whom we cannot see. It has also been suggested that the piece shows a"time lapse" wherein the two figures in the foreground first illustrate Kirchner (with his back to the viewer) approaching the women but then turning his back to them and seeks the viewer in a "plea for refuge."

Heckel's Landscape in Dresden (1910) underlies the group's affinity for Dresden, with its numerous bridges, as a location of choice for their inspiration. It depicts a figure walking over the merest suggestion of a bridge, a rose-red river receding into the distance in an otherwise flattened landscape of vigorous brushstrokes and sketchy details. Perhaps a literal representation of their group, the figure walks from the structured city life (represented on the left by a row of identical buildings) and over the bridge toward a disorderly wilderness and toward the freedom of a new expression and of color and form - and, more likely, to the future.

The remainder of the show illustrated a beautiful range of subject matter, from nature/landscapes and the group's escapes from urban life (such as to the lakes of Moritzburg and the island of Fehmarn) to the indoor scenes of the artists' studios. Schmidt-Rottluff's Country House in Osterholm (1906) presented a beautifully textured work that took on a wonderful three dimensional feel and that captured the lyrical freedom of impasto paint and the possibilities of the canvas. The last room included many images of Die Brücke's favored young model, Fränzi Fehrmann, such as Heckel's infamous Girl with Doll.

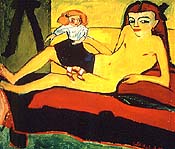

Left, Heckel's Girl with Doll (1910)

Right, Kirchner's Fränzi in Front of a Carved Chair (1910)

Here, Heckel's 9 or 10-year-old Fränzi lounges on a couch and looks out at us challengingly, her full-length nudity offset by the youthful ribbon in her hair and the child's doll that rests on her hip and conceals her genitals. However, this is not an exotic odalisque meant to incite sexual desire. The flat planes of color and the harsh, angular lines of her body reject classical representations of the female nude's long, sensuous limbs, soft curves, and carefully modeled forms. She exists as not a fantasy, but to encourage discomfort and outrage and to question the conventional bureaucracy of traditional art. The sexual nature of the work, however, cannot be ignored by the addition of a man's trousered legs that appear at the left. Kirchner's Fränzi in Front of a Carved Chair (1910) takes us to the other part of the spectrum with Fränzi in a green and red brightly patterned garment, her rouged face a sickly lime green. She stares out trustingly while the carving of the chair behind her head rises like an ominous force. Both works definitely look back at "primitive art" in its simple lines and expressive color. However, it was ultimately in the woodcut that the group found their muse. The long hallway on the third floor was devoted to the activity reports and portfolios composed by the group for their investors and other more passive members of their movement. Each one included a cover by one of the Brücke artists and contained woodcut and lithograph prints of another colleague. It is in this medium that embodied the startlingly raw nature of their craft, their avant garde intentions and their ultimate vehicle for expression.

No comments:

Post a Comment